Choosing Sustainable Landscaping Materials - and the moral dilemma involved!

Choosing sustainable landscaping materials can be challenging. There is so much often conflicting information out there, it can feel overwhelming. It risks taking the pleasure out of the garden design process. In this article, I share what I’ve learnt in my attempts to better understand the situation. This is less a ‘which materials to choose’ and more a ‘how to decide for yourself’! I hope this article also helps you to feel ok about the choices you make, knowing that no landscaping material or person is perfect!

Note: I talk about both hard landscaping materials (meaning paving, decking, walling etc.) and soft landscaping materials (trees, shrubs, soil etc.) in this article.

Why do we need sustainable landscaping materials?

In order to understand why we need sustainable materials we need to understand what problem they are trying to solve - the short answer is climate change. On average around the globe, the temperature is rising. According to the Met Office (a pretty reputable source when it comes to the weather):

All of the UK's ten warmest years on record have occurred since 2002 and heatwaves are now 30 times more likely (recording started in 1884).

UK winters are projected to become warmer and wetter on average, although cold or dry winters will still occur sometimes.

Summers are projected to become hotter and are more likely to be drier, although wetter summers are also possible.

Heavy rainfall is also more likely - since 1998, the UK has seen six of the ten wettest years on record.

It is now widely accepted that this is a result of increasing ‘greenhouse’ gasses in the atmosphere, mainly carbon dioxide and methane. We need a certain amount of these gasses to act like a natural ‘greenhouse’ and stop the planet from freezing. It’s also natural for levels of these gasses to fluctuate over time. However, carbon dioxide levels today are higher than at any other point in human history.

The last time atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were this high was 3 million years ago (pre humans). The greenhouse effect is increasing and causing temperatures to rise sharply with no sign of levelling out. The knock on effects of this change are many and complex. But ultimately, just as we see species become extinct when they can no longer survive in the context of environmental changes, the human race is at risk of serious harm and potential extinction.

Unless, that is, we can significantly reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impact of climate change effectively. To make a significant impact on climate change, governments and big businesses will need to act. But with over 8 billion people on the planet, the collective effect of individual actions can have an impact too. That’s where seemingly small choices like what landscaping materials we use comes in. Every little bit helps.

But this can leave us feeling morally burdened and overwhelmed and/or guilty. Not pleasant feelings and not feelings conducive to good decision-making. It’s understandable then that we might feel tempted to put our heads in the sand and ignore or deny climate change. We might get angry and look for someone to blame. Alternatively, we might feel like the world would be a better place if we just sat quietly waiting to die - until that is, we consider that even whilst waiting, we would be exhaling CO2! What to do?!

The moral dilemma

(Managing…)

We have to live. You’d have to have a really radical stance to disagree with that. So how can we manage the moral dilemma that living presents day-to-day when everything we do has an impact on the environment? How can we live without feeling ashamed of our choices? As a clinical psychologist turned garden designer, I feel I can say with a reasonable amount of confidence that shame never did anyone any good. I would also argue that a life completely devoid of joy, like the joy a beautiful garden can bring us, is no life at all.

I think we can attempt to manage the moral dilemma that living in the context of climate change presents, by trying to balance our desire to save the world (the great majority of us would if we could, right?), with the knowledge that no one person can do this alone. We can try to remember that there is no single ‘good’ life or ‘right’ choice. Just as biodiversity is essential for a healthy ecosystem, diversity is essential for a healthy society. I think the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated that it’s not always the obvious people who we rely on to keep society from falling apart. It really does take all sorts to make a world.

We are all the sum of our experiences. We all have different strengths and weaknesses. We all live in different contexts. There is no shame in that. It is part of the human condition. Likewise, we will all have different capacities for making environmentally informed choices, and that capacity will vary from day to day, moment to moment. Budget, time, access to information, competing priorities and responsibilities, mood, mobility, background, culture, taste, the media, desired and required function, existing conditions, planning restrictions, the weather, and a million other factors may have an influence on our decision-making and rightly so.

I think the important thing is that we see seemingly small choices like what landscape material to use, as an opportunity, not a burden. An opportunity, not to save the world (although do go ahead if you can!), but to factor sustainability into the decision-making process. That way, there’s a good chance we’ll make a decision that is a bit better for the environment than it might otherwise have been. Having worked in neuropsychology, I suspect that this sort of relaxed (brain) decision-making is likely to turn out best for everyone.

It may also help to remember that ultimately, well-designed gardens can be an albeit small part of the solution to climate change as I will discuss in this article.

Key questions to consider

As well as all the other factors which we need to take into account when designing our gardens (desired uses, budget, soil type etc etc etc), when it comes to choosing sustainable materials, the following are some key questions to consider.

1. How can we use, re-use, repurpose, or recycle the existing materials on site?

2. How can we minimise atmospheric greenhouse gases associated with using new material? Specifically in terms of:

Emissions (greenhouse gasses released into the atmosphere) during the production of the materials, including extraction, manufacturing, transport, and construction.

Emissions associated with the maintenance of the material.

Sequestration by the material (sequestration being the process of capturing and storing greenhouse gasses so that they are not in the atmosphere).

3. What will the lifetime of the material and the project be, and what will happen next?

4. How will the use of the material help us to mitigate (make less severe or serious), and/or adapt to the impact of climate change?

I have provided some information below which I hope will help you to consider each of these questions. I use the term ‘consider’ because all this is complex, and I don’t think feeling pressured to come up with definitive answers to any of this stuff is helpful!

1. How can we use, re-use, repurpose, or recycle existing materials?

Often, the most sustainable approach is to use clever design to make the most of the existing materials we already have on site. This might mean re-using, re-purposing, recycling, or renovating materials, or leaving aspects of an existing site more or less untouched. This approach avoids the typically significant greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of new materials. The approach also has the potential benefits of saving money, adding maturity to your garden, and maintaining a sense of history.

For example, take trees; A tree may take from 15 to 40 years to reach maturity. By comparison with a small young tree, mature trees are expensive to purchase, take more resources to transport, take more resources to establish (potentially including a relatively unsustainable irrigation system), and are more likely to die before they become established. By retaining existing trees (preferably not moving them) and working them into a beautiful new design, you’re saving money, giving your new garden a sense of instant maturity, and potentially maintaining hundreds or even thousands of years of history.

Here are just a few ideas for making the most of existing landscaping materials (possibilities not ‘shoulds’!):

Existing hard landscaping (paving, paths, steps) might be renovated (e.g. giving a cobbled path a good weed), reused (e.g. in the case paving slabs laid on sand), repurposed (e.g. using bricks from a wall as edging), or recycled (e.g. crushed and used as hardcore).

Soil might be retained on site, unmoved, or where there is a risk of compaction or contamination, piled up, to be redistributed at an appropriate time.

Plants including trees, shrubs, and hardy perennials might be kept, renovated, and/or transplanted.

Woody ‘waste’ might be turned into wood chip for paths or mulch, or in the case of brush cuttings and pruning’s, turned into a ‘dead hedge’, with ‘Dead wood’ (fallen trees and branches, log piles etc) being incorporated into the design as sculptural/structural forms (the picture above is of the wonderful wave-like log piles in Professor of Planting Design and Urban Horticulture, Nigel Dunnett’s own garden)

Many of these approaches not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with new materials, but also have important benefits in terms of greenhouse gas sequestration and/or biodiversity too (read on for more information about this).

2. How can we minimise greenhouse atmospheric gases associated with new materials?

Detailed analysis and rules of thumb.

The Climate Positive Design Pathfinder tool

Calculating the environmental impact of your project anywhere near accurately is incredibly difficult. I attended a Society of Garden Designers workshop in 2023 which introduced the Climate Positive Design Pathfinder tool. This is intended as an early-stage design tool which enables users to compare design alternatives in terms of ‘contribution to climate change’.

I note that other promising tools have since been developed since 2023, such as Elemental , and that tools have been integrated into design software such as Vectorworks. When I get a minute, I’ll revise this blog to cover these in more detail, but for now, my takeaways from the Climate Positive Design Pathfinder tool (which has itself been updated since I wrote this!) will have to do.

Whilst designed for use with large scale landscape projects, I felt the pathfinder tool looked potentially manageable for use with domestic garden design projects, and it’s free! If you don’t feel you can justify the added time required to use the tool, I would still highly recommend visiting the Climate Positive Design website for some helpful rules of thumb including:

The Climate Positive Design Toolkit

The Climate Positive Design Toolkit is packed with information relevant to minimising the greenhouse atmospheric gases associated with new materials, but also covers related areas (some of which are discussed elsewhere in this article), including climate resilience, equity, and advocacy. It might not all be for you, but you can pick and choose.

Bear in mind it’s American. For example, ‘Decomposed granite’ is a hoggin type material, the natural derivative of granite as it weathers and erodes over time - more collected than quarried. Sounds great but rarely found in Europe. The closest equivalent near me in Cornwall would probably be self-binding gravel produced from locally quarried granite waste - different environmental implications.

The Landscape Carbon Calculator Data Report

The Landscape Carbon Calculator Data Report is also packed with information including the following non-exhaustive list of strategies/best practices for:

Reducing Embodied Carbon / emissions (of greenhouse gasses) associated with the production of the materialReduce concrete, stone, steel and foam (carbon-intensive materials)

Reuse/salvage materials from other projects

Substitute cement with fly-ash, slag, glass pozzolan or other cementitious materials in the concrete mixes

Use more wood as a substitute for concrete or metals

Consider gravel, terrazzo, asphalt or other aggregate-based paving (trade-off with heat island reduction)

I would add that considering the transport of materials from source to the processing site, supplier, and to your site is an important factor relative to your individual situation. Buying locally sourced materials may reduce transport related greenhouse gas emissions and help to support local businesses!

Reducing Operational Carbon / emissions associated with the maintenance of the materialUse electric-powered equipment instead of gas-powered

Ensure that electricity is coming from clean sources

Limit the use of fertilizer; reuse mulch produced from pruning and trimming

Select vegetation that does not require extensive maintenance and fertilization

Increasing SequestrationPlanting more trees that can grow to taller heights (35+ ft)

Selecting species that have longer growing seasons in that region

Planting woody shrubs

Ensuring proper care during establishment periods to increase survival rates

Selecting trees with known long lifespans

Salvaging wood from fallen trees

Selecting lawn types that require lesser fertilizer application and maintenance

Constructing wetlands

In case it’s not obvious from the above, I would add the general rule of thumb that using more planting and less hard landscaping tends to be more sustainable, with the proviso that we work with the existing contours of the land as far as possible, thus doing less earth movement (which releases greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere and requires the use of heavy machinery which also has a relatively high carbon footprint and causes soil compaction).

3. What will the lifetime of the material and the project be, and what will happen next?

This is really 3 related questions in one, all of which can be tricky to answer…

What will the lifetime of the material be?

A material that only lasts a short time may need to be replaced, so whilst it may seem an environmentally sound choice, it could end up being less sustainable than a material that will not need to be replaced. Having said this, we also have to bear in mind that we need to buy the human race time in the race to address climate change, so as to avoid climate ‘tipping points’.

Tipping points are points at which changes in a part of the climate system become self-perpetuating (even if we do then reduce greenhouse gas emissions). These changes may lead to abrupt, irreversible, and dangerous impacts with serious implications for humanity. For example, the collapse of the Greenland, west Antarctic and two parts of the east Antarctic ice sheets. Therefore, it’s generally agreed that emitting a quantity of greenhouse gasses today, is worse than emitting the same quantity of greenhouse gasses after a decade.

What will the lifetime of the project be?

If the project is going to be scrapped after a short time, a material that lasts a short time but otherwise has good sustainability credentials may make more sense. Likewise, a long-lasting material may make more sense for a long-lasting project, although again, we need to bear in mind climate change tipping points. For that reason, renewable materials (i.e. bio-based materials such as timber, bamboo etc.), may be a good option as they can be replaced at relatively low cost to the environment.

However, theoretically renewable materials need to be carefully selected to ensure they will indeed be renewed! For example, for optimal sustainability, timber should be sourced as locally as possible and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified, confirming that the source forest is being managed in a way that preserves biological diversity and benefits the lives of local people and workers, while ensuring it sustains economic viability.

What will happen next?

It’s often very hard to predict. What will happen to the materials used in a garden at the end of the life of the material? What about at the end of the life of the garden? More specifically, what will be the associated greenhouse gas impact on the atmosphere through any deconstruction, demolition, transport, waste processing, disposal, reuse, repurposing, renovating, or recycling involved? The designer, be that a professional or the homeowner themselves, may not be involved at that point.

We can however choose materials (and construction methods) which will lend themselves to sustainable solutions. For example, choosing paving which can be laid on sand (with the added bonus of being permeable) so that it can be lifted and reused, or choosing renewable materials which can ultimately biodegrade and be replaced at a relatively low cost to the environment.

4. How will the use of this material help us to mitigate and/or adapt to the impact of climate change?

Gardens can be part of the solution!

Climate change will impact/is impacting on the UK in a number of ways including:

Low lying and coastal regions are particularly at risk of flooding.

More droughts mean greater water scarcity.

Loss of biodiversity (the variety of life on earth) - climate change and the causes of climate change threaten numerous species (not just humans) with extinction due to loss of the conditions and habitats which can sustain them. This is an indirect threat to us as we rely on the interdependent web of biodiversity in all its forms (including plants and wildlife) for our survival.

Most garden design projects will increase the amount of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere initially which is obviously a concern, particularly in the context of tipping points (see above). However, we have to live (see above), and the wonderful thing about well-designed gardens, is that they can be part of the solution.

A well-designed garden can help us mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change, for example through; habitat creation increasing biodiversity, drought tolerant planting and planting trees for shade, and creation of sustainable drainage solutions (SuDS) which help to prevent flooding (e.g. permeable paving, green roofs, ponds, rain gardens, swales, and rainwater harvesting including water butts and underground storage tanks).

Through ongoing greenhouse gas sequestration by trees, shrubs, lawn and wetlands, we can hope to eventually reach a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas that's produced in connection with the construction of a garden, and the amount that's removed from the atmosphere - net zero, and then go on to actually reduce the amount of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere - become climate positive, in time.

However, it’s important to remember that the less upfront greenhouse gas emissions we cause in the creation of our gardens, the quicker we’ll get to net zero and become climate positive. The image above, one of the Climate Positive Design Case Studies, shows how a garden design went from 22 years, to 5 years, to becoming Climate Positive. Design Improvements led to:

23MT of C02 not released

153MT of additional sequestered C02

44% reduced footprint

52% increase in sequestration

17 years off carbon neutral point

All is not necessarily what it seems

As described above, understanding the degree to which a material is sustainable is complex and we won’t always know the whole picture. Sometimes, materials which appear sustainable turn out to be less so, and sometimes materials which appear unsustainable turn out to be more so. All we can do is try to educate ourselves and make decisions as they arise as best we can.

Manufacturers and suppliers increasingly have environmental policies and/or will be able to provide various certifications e.g. Environmental Product Declarations and Life Cycle Assessments, which can help us to understand the pros and cons of various materials. Beware of greenwashing though, the ‘green industry’ has become big business - genuinely ‘green’ companies should be able to back up their claims with facts and figures - saying something is ‘green’ doesn’t make it so!

A common mistake is thinking ‘natural’ means ‘sustainable’. Not necessarily. For example:

Existing natural sandstone slabs which are reused in a new design for the same site, might be extremely sustainable, but sandstone quarried in India with heavy machinery (and potentially using child labour), destroying habitants and ecosystems, before being transported thousands of miles to a supplier in the UK based some distance from your site, which is laid on cement and doesn’t last long because it is poor quality (it’s cheap for a reason), is not at all sustainable.

Natural FSC certified oak or Douglass fir timber from a forest near you might be a relatively sustainable choice but tropical hardwood timber, from 800 year old trees felled in ancient rainforests, causing the destruction of habitats and ecosystems, and then transported thousands of miles to a supplier in the UK based some distance from your site, is not at all sustainable - in this case certification is not enough.

Likewise, native plants and trees might seem like a good idea and very often are as they support our wildlife, but in an age of biodiversity loss and shifting climate, it’s also important to consider planting non-natives for drought tolerance and to extend the flowering season for pollinators. What we think of as ‘native’/originating in the UK has evolved throughout history. For example, Galanthus nivalis (snowdrops) often found wild in woodlands and thought of as a British native, was imported many years ago. I find it a sobering thought that a tree which may live for hundreds or even thousands of years, will need to be able to tolerate the changing climate over that time, long after I’m gone.

Looks can be deceiving

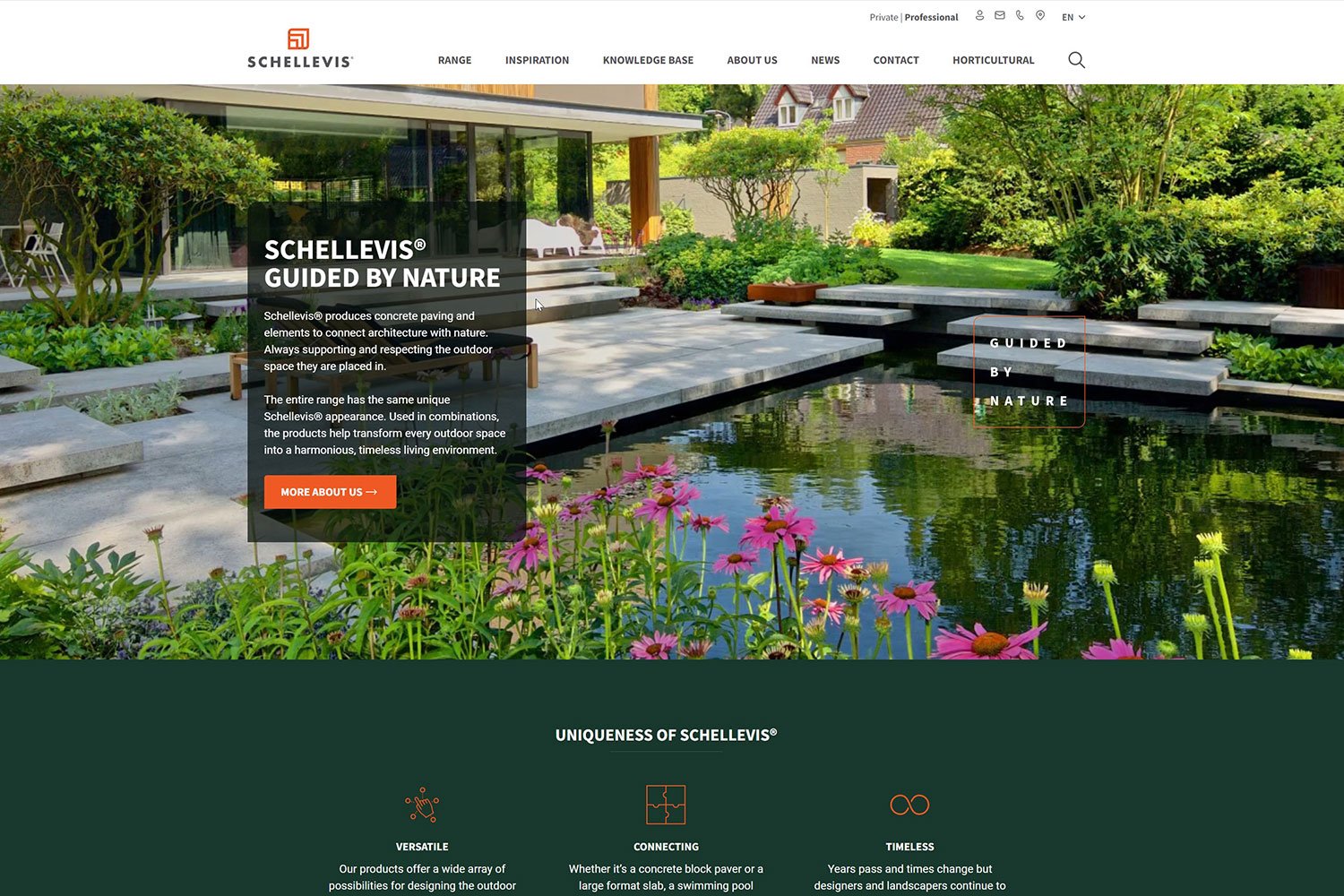

Schellevis: A case example.

Disclaimer for this next bit: I’m not receiving any payment or free products from any of the companies or organisations mentioned; Schellevis, Lowarth Landscaping Supply (a supplier of Schellevis), London Stone, Carbon Footprint, or the Concrete Sustainability Council! I do thank them for their help in providing information for this article though.

A great example of where a ‘non-natural’ product can have surprisingly good sustainability credentials is provided by Schellevis. You could be forgiven for thinking that all concrete products are bad given the upfront greenhouse gas emissions associated with traditional concrete. I first came across Schellevis when they hosted an event at Lowarth Landscaping Supply to showcase their range. I was impressed by UK Business Development & Specification Manager Ryan Burge’s explanation of how Schellevis is no ordinary concrete product:

Based in the Netherlands, the majority of Schellevis’ transportation takes place by boat (low carbon emissions), and they source raw materials as locally as possible (e.g. pigments are a biproduct of the steel industry sourced from Germany instead of China). Their internal transport consists largely of eclectic forklift trucks and bikes.

50% of the sand used is ‘secondary’, coming from recycled crushed concrete.

50% of the sand used is locally sourced ‘fresh’, but Schellevis try to avoid quarried sand where possible, instead preferring sand produced as a biproduct from canal expansion.

50% of the aggregate used is from recycled crushed concrete.

Only 15% of the total mix is cement and they are testing non-cement ‘fillers’ with the aim of reducing their cement content by 30-40% - these are ash from incinerated waste and recycled tarmac, they do not use fly ash as they feel this ‘props up’ the coal industry and would make their product heavier thus increasing emissions associated with transport.

No heat is required in the manufacture of their product (unlike ceramic tiles for example).

Their product is extremely long-lasting and durable and can be recycled or reused (e.g. if pavers are laid on Type 1 or ideally Type 3 for greater permeability)

Since 2016, Schellevis have held an NL Greenlabel, and they were one of the first producers of concrete slabs to have been awarded the Concrete Sustainability Council (CSC) certification back in 2022. They were awarded Silver at that time, but have continued to make improvements to their product and feel confident that when retested in 2024, they will achieve the highest rating, platinum.

At the time of testing by the CSC in 2021, 50mm Schellevis slabs were found to have a carbon footprint (embodied carbon) of 20kg per sq m (they believe it would be much improved now). Whilst it’s a little like comparing apples and pears, and no system of measurement is perfect, I’ve shared some information below from London Stone, a leading company in providing environmental and ethical credentials, who partnered with Carbon Footprint to provide Life Cycle Assessments of some of their products.

38mm British Yorkstone - 10.75 average Kg CO2 per m2

20mm Brazilian slate - 13.11 average Kg CO2 per m2

22mm Indian riven sandstone - 20.39 average Kg CO2 per m2

25mm German Jura Limestone - 22.58 average Kg CO2 per m2

40mm British Portland Limestone - 25.45 average Kg CO2 per m2

20-25mm Indian sawn Sandstone - 25.59 average Kg CO2 per m2

20mm Italian porcelain - 25.60 average Kg CO2 per m2

25mm Indian riven limestone - 27.37 average Kg CO2 per m2

20mm Indian porcelain - 52.49 average Kg CO2 per m2

So if we take these statistics at face value, Schellevis, a concrete product, looks surprisingly good when compared with many natural stone or porcelain alternatives and according to their UK Business Development & Specification Manager Ryan Burge, they are constantly working to improve their carbon footprint (I note that at the time of writing, their Sustainability web page was out of date). In addition, because so much of their raw material is recycled, Schellevis has the benefit of not requiring the destruction of as much habitat and ecosystem in it’s manufacture as is typical of natural stone quarrying.

A note on Carbon Offsetting

‘Carbon Neutral’ is not the same as ‘Net Zero’. Carbon offsetting is the act of reducing or removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere to compensate for emissions made elsewhere. Companies can claim to be ‘Carbon Neutral’ purely on the basis that they offset equivalent emissions released into the atmosphere from their activities with no effort to reduce upfront emissions at all. There has been quite a bit of controversy about carbon offsetting as I’ll discuss in this section.

Quite a few carbon offsetting schemes were found in the past but also more recently, to be ineffective or even counterproductive and ethically dubious for a wide variety of reasons - Wikipedia has quite a good discussion about this in the ‘Limitations’ section of their Carbon Offsets and Credits page. In short, it’s not as simple as planting a few trees.

There has also been criticism of projects which do not turn out to be making an impact on atmospheric greenhouse gasses beyond what would have happened anyway. To give a small-scale example, changing to energy efficient lightbulbs to ‘offset’ a flight when you were going to change to energy efficient lightbulbs anyway is not offsetting, there is no ‘additional’ benefit to the environment.

In 2016 as many as 85% of Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects (a United Nations-run carbon offset scheme) were found to have a low likelihood that emission reductions would be additional and not over-estimated. Only 2% of the projects had a high likelihood of ensuring that emission reductions were additional and are not over-estimated.

Increasingly though, effective and ethical offsetting projects are being created, often in connection with clean energy, designed to make quicker and more permanent savings than planting trees, and, as a bonus, to offer social benefits. However, the question then is, shouldn’t these sorts of projects be being carried out anyway by governments? This would then leave us (companies and individuals) free to focus on reducing our upfront greenhouse gas emissions.

From the perspective of tipping points (as discussed above), it is particularly important to focus on reducing upfront greenhouse gas emissions now. The benefits of offsetting methods that take time to deliver, may come too late to avoid catastrophic changes associated with tipping points.

Companies are more sustainable when they can demonstrate net zero emissions, meaning that greenhouse gas emissions have been reduced as far as possible, with offsetting used effectively only to re-absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere where unavoidably emitted. Ideally of course a company would be climate positive, doing more good than harm when it comes to the associated amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, like well-designed gardens can be!

Summary

What we can do.

The climate is changing, which presents a threat to human beings both directly (e.g. through flooding and droughts) and indirectly (e.g. through biodiversity loss). To tackle climate change, we need to significantly reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impact of climate change effectively. Whilst action from governments and big business is needed, the choices of the more than 8 billion people on the planet can make a difference too.

This presents a moral dilemma; how can we live knowing everything we do has an impact on the climate? We can navigate this dilemma by seeing seemingly small choices like what landscape material to use, as an opportunity not a burden. We can remember that it takes all sort to make a world. We can celebrate any effort that any individual feels able to make to factor sustainability into their day-to-day choices, whilst being compassionate in recognising that it’s not always easy.

When choosing landscaping materials, we can ask ourselves 4 key questions:

How can we use, re-use, repurpose, or recycle the existing materials on site?

How can we minimise atmospheric greenhouse gases associated with using new materials?

What will the lifetime of the material and the project be, and what will happen to it next?

How will the use of the material help us to mitigate and/or adapt to the impact of climate change?

We can do our best to educate ourselves. We can bear in mind that all is not necessarily what it seems, that ‘natural’ and ‘green’ don’t necessarily mean ‘sustainable’, and that ‘native’ isn’t always best. We can ensure we don’t judge materials purely by appearances and encourage companies to pursue more sustainable solutions. We can understand that ‘net zero’ is preferable to ‘carbon neutral’ and that ‘climate positive’ is ideal.

Best of all, we can remember that well-designed gardens can be an albeit small part of the solution to climate change!

Please don’t hesitate to get in touch if you have a project you’d like to discuss or if you’d like to book me as a speaker. I’d love to hear from you!

If you have any questions, if you think there is anything missing or inaccurate, or if there is anything else you’d like to see included, I’d welcome your comments below.